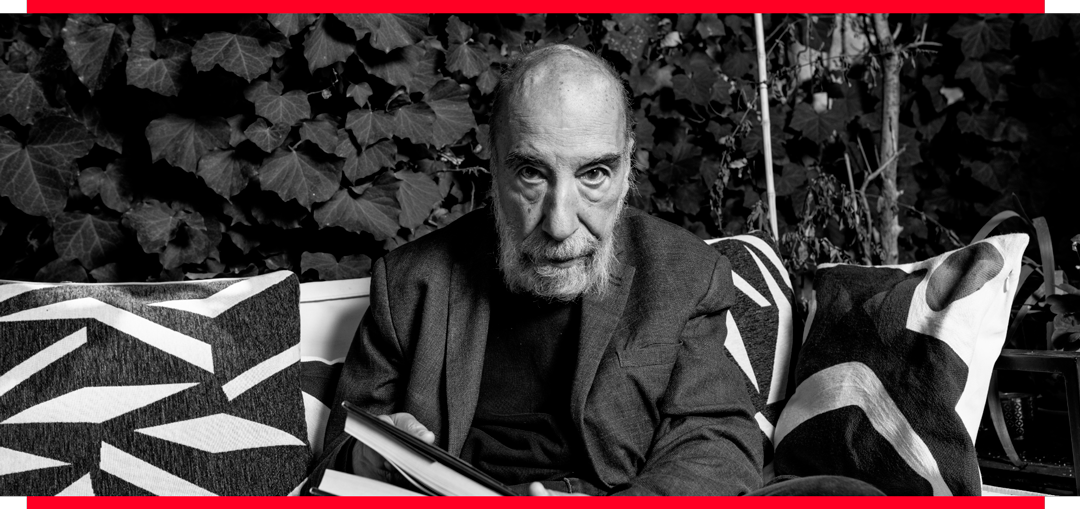

In the shade of his overgrown garden, with the autumn wind pushing its way through the trees, Raúl Zurita Canessa expresses himself almost in whispers, although with intense words. “Poetry and human rights are the same thing,” our country’s most important living poet affirms immediately. And he continues: “Poetry and human rights have gone together since the beginning of time; it has to do with that mixture that we are, of horror and wonder, that is always with us.”

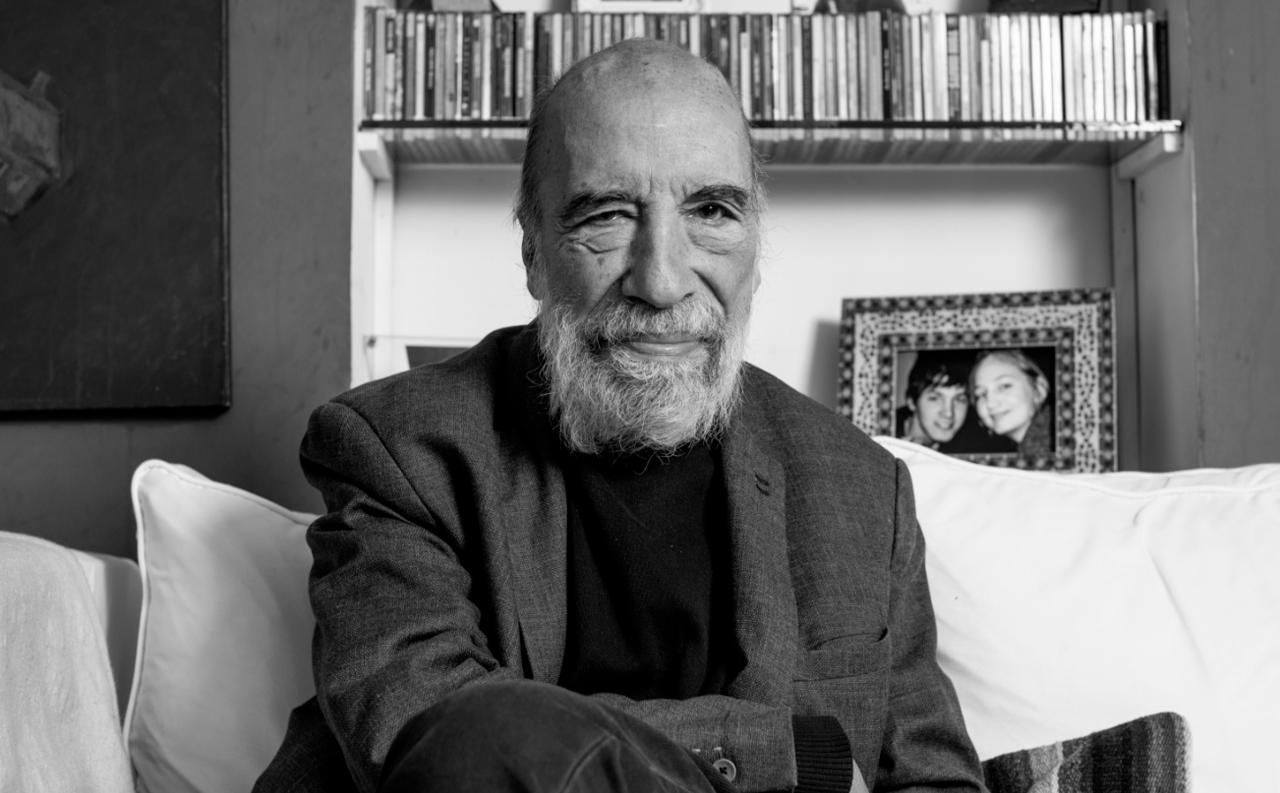

He is author of Purgatory (1979), Anteparadise (1982), The New Life (begun in 1982 and concluded definitively in 2018), Song of Love Gone (1985), INRI (2003) and Zurita (2011), to mention just some of his works. Among the long list of awards that he has won are the National Literature Prize (2000), the Reina Sofía Prize for Ibero-American Poetry (2020) and the Pedro Neruda Ibero-American Poetry Award (2016).

Of course, his artistic acts have also elevated him to the status of a living legend. For the publication of his first book, Zurita appeared on the cover with a scar on one of his cheeks, the product of a self-burn. Or when he poured ammonia in his eyes and nearly went blind. Or on June 2, 1982, the day that the first fifteen verses of his poem The New Life were written in white smoke in the New York sky by five planes. The fame of a literary rockstar also accompanied him during the social protests of 2019, when a photo of him walking among the crowd with the Chilean flag raised high went viral on social networks.

Santiago will be the guest city of honor at the 2023 Buenos Aires International Book Fair, and on Saturday, April 29, Raúl Zurita will recite his famous Song of Love Gone, considered a cry of resistance against the military dictatorships that the continent suffered between 1970 and 1990. It will be a personal reading, remembering that the history of the Latin American continent is marked by violence, oppression and hunger.

—It is interesting what you said about the unity between poetry and human rights. How else are they related?

—Poetry is the hope of those who have no hope, the love of those who lack love, that tenuous thread that, despite everything, makes you persist and persist in life, to the point that some have not endured it. Because the history of poetry is also a tragic one; there are stories that are terrible. Look at the Greeks, at The Iliad, which is brutally violent.

He remains thinking and, staring fixedly, states:

—The greatest poem would have been that those terrible books had never been written. It would mean that what was being narrated never happened; however, poetry has to bear all those flaws. There’s a terrible phrase from The Iliad: “It is as if the gods take pleasure in causing us suffering, because they love the sound of our songs.” Because the song is also born from pain (…) Some say that without a wound, there is no art; and it’s possible that is the case, because if everything is closed, poetry would have nowhere to come out… But you don’t only talk about your wounds; poetry goes on remembering all those moments when one man took another’s bread, up to the present day. I mean poetry understood as art in general.

“I suffered some ferocious beatings, but I didn’t suffer torture”

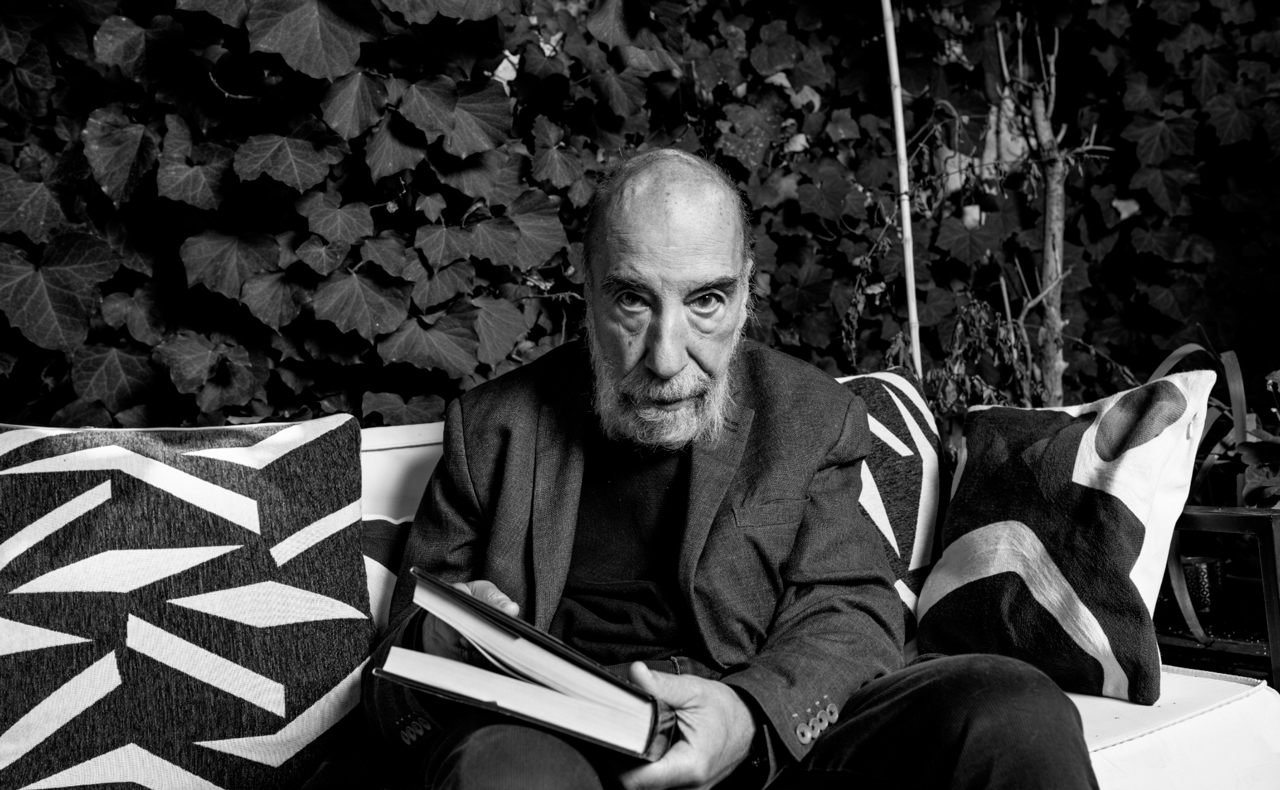

On September 11, 1973, Zurita was heading towards the Universidad Técnica Federico Santa María de Valparaíso, where he was studying Structural Civil Engineering, when the military took him prisoner. It was at that moment that the story of the young communist militant took another turn.

—Were the agents of the dictatorship looking for you?

—No, it was completely random. They were after anything that moved, and I was unlucky enough to be in the wrong place at the wrong time. They took me when I was trying to go to the university at six in the morning, because I’d spent the night without sleeping and I wanted to go have breakfast. They took me and it was all horrible; I suffered some ferocious beatings, but I didn’t suffer torture. I want to make it clear; that didn’t happen to me. It was a time of barbarians. Everyone remembers the fear, the horror, the physical insecurity; but no one mentions the poverty. Since I could no longer go to university and I was jobless, the hunger was unbearable. I had a wife, three children, and I needed to make money any way I could. I didn’t plan to write, not at all. I didn’t give a damn about it; but in desperation I wrote and wrote… I think I became a poet out of despair, and real despair. Afterwards, poetry was for me a way of not giving in, of not going crazy… I first published in 1979. I came up with the craziest things, like writing in the sky, and I actually did them. It was incredible. All that insanity kept me upright in the face of anguish and, above all, poverty.”

That was when Zurita formed the Colectivo de Acciones Artísticas (Artistic Actions Collective, CADA), together with Lotty Rosenfeld and the writer and National Award winner, Diamela Eltit, his second wife, with whom he had his fourth child.

“It was a time, and this is going to sound weird, that was darkly exciting. It was such a dark time that the only thing you had was your friend or partner, because everything outside was horrible. I remember those conversations on the verge of curfew, where you could dive into the depths of what we are; and it’s incredible, because it awakened a solidarity among us, a fraternity… We passed the night, crouching close to each other. That time is part of me.”

—Those were also the days of your already mythical artistic expressions, when you affected your own physical integrity.

—I never did a performance, as it’s now called. The things I did were absolutely solitary, locked in a room, without an audience, nothing. What did I do with the despair? Because we artists are not able to bear so much darkness either; and to bear it, it’s because, despite everything, there’s something that shines somewhere, love, the face of someone you love, very simple things and, at the same time, the most profound things in the world. The role of poets, like that of singers, is to maintain the spirit, and the soul as well.

—Did you manage it?

—Well, I’m here; I survived my own self destruction… In a country where so many people disappeared, all the rest of us speak as survivors, because it could have been any of us. In a world of victims and victimizers, the poet must be the first victim; but also the first to rise and say that, despite everything, better days will come. For me, it’s the conjunction between despair and hope…

—How do you interpret the rise of fascism and autocracies in the world today?

—It’s really quite a hopeless world, which affects us all. In war, there are such heart-breaking, terrible scenes. In Ukraine, I remember seeing a completely demolished house, with an old lady inside who could barely move. One of the rescuers took her hand, but they had to go and she told him: ‘Please, stay a little longer, because when you leave, I will only have the night and the terror. This was my house, where I’ve always lived, and now I’m going to die without someone to hold my hand…’ Faced with such real scenes of pain, one bends down. In this world full of bombs and madness, the living are survivors… Whether we survive for better or worse remains to be seen. Art in this sense is the most tremendous, terrible and exact representation of the world in which we live. And the fact that we make art is already something. He pauses. “There is a lot of talk about memory, that this generation has no memory. I don’t think it’s like that. Through mysterious channels, everything is remembered.”